All You Need To Know About Zombies: The History And Myths

While George Romero is often credited as being the one to give birth to the zombie with his 1968 film Night of the Living Dead, the zombie actually goes back much further than that and its’ origins run much deeper than simple entertainment. Zombies have a rich history and not all of it is pleasant-in fact a lot of the implications that come with it aren’t-but still, it is deeply interesting.

The Term ‘Zombie’ is Derived from West African Languages

It is thought that the modern term ‘zombie’ has roots in the Kongo language as well as the Mitsogo language of Gabon; 'nzambi' translates to the ‘spirit of a dead person' in the Kongo language, while 'ndzumbi' means ‘corpse’ in the Mitsogo language. Significantly, both these areas were places where European slavers would transport the native people they had captured to the West Indies, forcing them to work on sugar cane plantations.

‘Zombie’ was Brought into the English Language by Robert Southey

Robert Southey published a novel in 1819 titled A History of Brazil, in it he used the word zombie-spelled ‘zombi’ without the E-to refer to mindless corpses that had been reanimated. Though, a writer named W.B. Seabrook claims he is the one responsible for popularising the term, using it in his sensationalist travel narrative about his trip to Haiti in 1927: The Magic Island.

Slaves were Forced to Convert to Roman Catholicism but Continued Practicing their own Religions

Haiti used to be occupied by France and was called St Domingue after the French Saint-Domingue. French law at the time meant that slaves had to convert to Catholicism; however African slaves continued to practice their own religions as well, resulting in the creation of new religions that were a mixture of traditions e.g. Vodou/Voodoo in Haiti, Obeah in Jamaica, and Santeria in Cuba.

Vodou combined the West African belief system of Vodun with Roman Catholicism, it also contained elements of what came to be called ‘black magic,’ which included various rituals like the creation of zombies. This was the part of the religion that most captivated American audiences and became the influence for Hollywood’s portrayal of the religion-though it is warped so much it is barely recognisable compared to true Vodou.

Zombies are Part of Vodou

Due to the influence of Vodou in Haiti, there are many stories about zombies in Haitian culture. Vodou dictates that bodies can be brought back from the dead by a Vodou sorcerer called a Bokor; unlike what is portrayed in media, these zombies aren’t dangerous or cannibalistic. The zombies in Vodou tales are reanimated bodies who had no free will, they were mindless slaves belonging to the Bokor who created them, obeying their creator’s demands.

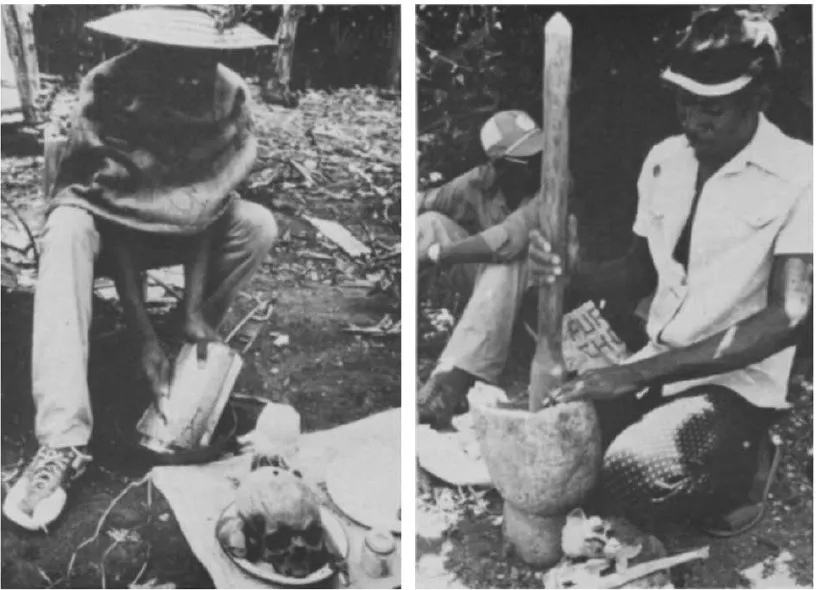

Bokors Create Zombies using Souls

A Bokor can create a zombie by removing or taking possession of their victim’s soul, some stories claim this is done while the victim is alive, others state that the process starts after death. Often, the act of zombification was said to be used as the victim’s punishment for acts they committed against the Bokor while they were living.

The Bokor would subdue their victim using a powder or spell that would suppress their heart rate and breathing and drop their temperature so much that the victim would appear dead. Once the victim was officially deemed to have died and been buried, the Bokor would dig up the body; as a consequence of going through this process, the victim’s memory would be eradicated, leaving them as a mindless shell for the Bokor to use as a slave.

The BBC states: ‘The zombie, in effect, is the logical outcome of being a slave: without will, without name, and trapped in a living death of unending labour.’

Traditional Zombie Characteristics

Traditional zombies made by Vodou sorcerers can only understand basic commands and have a limited vocabulary, mainly communicating through moans and groans. They are stronger than humans and are not very responsive to stimuli, which makes them virtually resistant to pain and exhaustion.

However, they are slow and clumsy, using uncoordinated, repetitive movements and displaying fixed, vacant expressions. Once a person becomes a zombie they are left in a dreamlike trance and have no awareness of their condition, they are submissive and contrary to those seen in media-rarely attack people unless commanded to by the Bokor controlling them. If/when their Bokor dies, zombies can regain their freedom.

The Haiti Revolution Started in 1791

The conditions for slaves in St Domingue were so awful and the death toll of slaves was so high that eventually a slave rebellion was initiated and in 1791 they overthrew their masters. Consequently, the country was renamed Haiti and, after a revolutionary war that lasted until 1804, it became the first independent black republic.

However, after that the country was consistently depicted as being violent and superstitious, demonised by European Empires. For the majority of the 1800s accounts asserting that black magic rituals, cannibalism, and human sacrifices were occurring in Haiti were commonplace.

America Occupied Haiti in 1915

After America occupied Haiti in the 20th century, the American forces tried to destroy the native Vodou religion; however, this only succeeded in making it stronger. At the same time, the rumours of violence and ritual sacrifice, etc. started to centre around the entity of the zombie.

Significantly, in 1932 two years before America ceased to occupy Haiti in 1934, the film White Zombie was released. This showed that, while America had the intention of modernising what they considered a barbaric and primitive country, they were influenced by the very culture they sought to cull.

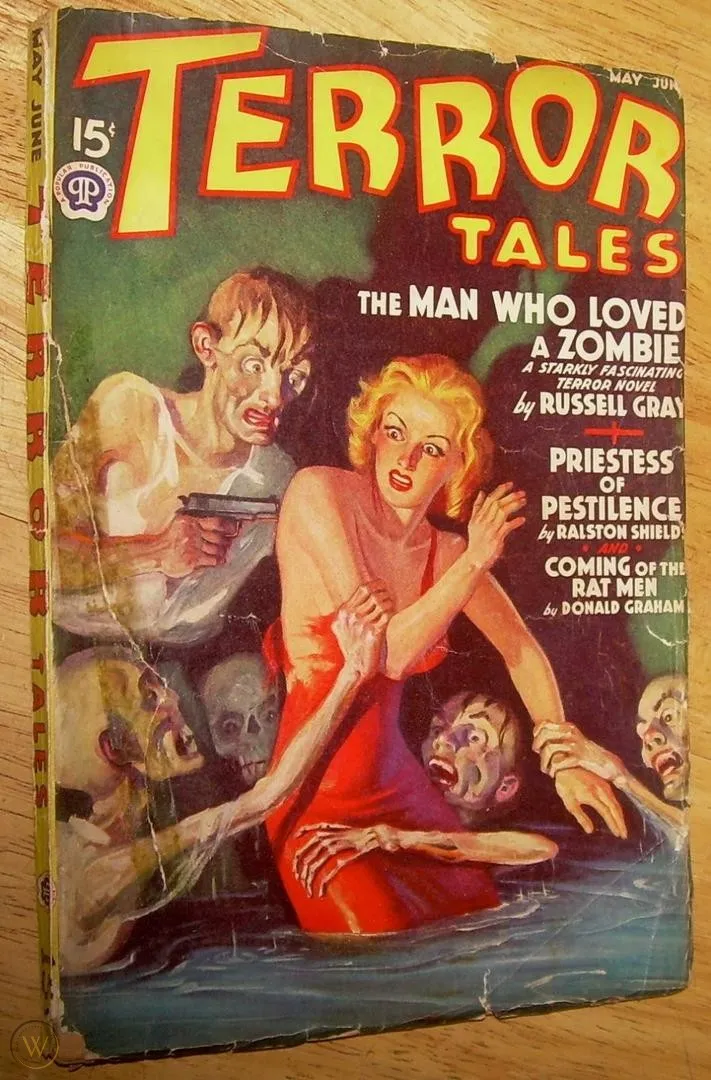

Zombies Replaced Ghosts in American Pulp Fiction

Throughout the 1920s and 30s, stories featuring the rising of vengeful dead became more and more common. Whereas before the dead who sought revenge in the narratives took the forms of ghosts and malevolent spirits, now they had physical forms composed of decaying flesh, clawing their way out of their graves through the earth.

However, the real thrill didn’t come from writers of horror magazines, but from writers who claimed to have actually come into contact with zombies in the real world.

Writer W.B. Seabrook Claimed to have Encountered Zombies on a Sugar Plantation

William Seabrook was a journalist and writer, as well as an occultist and alcoholic who wrote The Magic Island in 1927 about his trip to Haiti. He took pleasure and excitement from visiting what was regarded as ‘primitive’ countries/cultures, places such as Arabia and West Africa.

When he visited Haiti, he not only claimed to have been possessed by a God but also that he came into contact with zombies, the account of which was recorded in a chapter called 'Dead Men Working in Cane Fields.' One night, a local took Seabrook to Haitian-American Sugar Corporation’s plantation to meet the ‘zombies’ who worked the fields at that time.

“They were plodding like brutes, like automatons. The eyes were the worst. They were in truth like the eyes of a dead man, not blind, but staring, unfocused, unseeing.” - W.B. Seabrook

This was how Seabrook described them before reassessing them and revealing them to be ‘ordinary demented human beings, idiots, forced to toil in the fields.’ The chapter formed the basis for the previously mentioned film White Zombie.

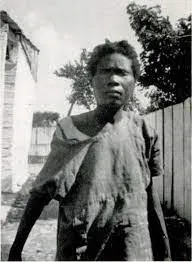

Zora Neale Hurston Believed she met a Zombie in a Haitian Mental Hospital

Before travelling to Haiti, Zora Neale Hurston had trained as an Anthropologist and had already done a study on Hoodoo in New Orleans, she then went to Haiti with the intention of becoming a Voodoo priest. In her book about Haiti Tell My Horse (1937), Hurston explains that she ‘had the rare opportunity to see and touch an authentic [zombie] case.’

I listened to the broken noises in its throat, and then, I did what no one else has ever done, I photographed it.” - Zora Neale Hurston

The photograph was of Felicia Felix-Mentor, and soon after Hurston met her, she left Haiti, claiming that secret voodoo societies were determined to poison her.

How Zombies and Haitian Culture are Portrayed in Films

Zombies became a staple of horror, but unlike today where they are cannibalistic and violent, early zombie films showed zombies as ordinary people who had fallen under voodoo spells, with the concept of becoming a zombie being the fearsome aspect, not the fear of being eaten by them.

‘While the original zombie is a powerful metaphor for fears of the non-white Other and reverse colonization, the contemporary zombie largely reflects contemporary fears of loss of individuality, the excesses of consumer capitalism, environmental degradation, the excesses of science and technology, and fears of global terrorism (especially more recent renditions of the zombie post-9/11).’ - David Paul Strohecker

While other monsters may grow to become obsolete in the horror genre, zombies are constantly being revigorated, reflecting contemporary fears and anxieties. And though the fears the zombies represent continue to change and be reinvented, the zombie itself will always have its roots in Haitian culture and history.

Opinions and Perspectives

I had no idea zombies originated from West African languages. Always thought they were just a Hollywood creation.

The connection to slavery and forced labor is pretty haunting when you think about how zombies are portrayed as mindless workers.

Fascinating read. The way Vodou was demonized by European empires shows how cultural misunderstanding can create lasting stereotypes.

Never realized there was such a big difference between traditional Haitian zombies and modern movie versions. The original concept seems way more terrifying to me.

That quote about zombies being the logical outcome of slavery really hit me hard. Makes you think about how horror often reflects real historical trauma.

Interesting how zombies kept evolving to reflect different societal fears. From slavery to consumerism to terrorism, they're like a mirror of our anxieties.

You make a good point about the evolution. I find it fascinating how they went from being controlled by a single Bokor to becoming this mindless horde we see today.

The part about slaves being forced to convert to Catholicism but maintaining their traditions shows such incredible resilience.

Im surprised the word zombie has been around since 1819. Thats way earlier than I expected.

Anyone else find it ironic that America tried to destroy Vodou culture but ended up being heavily influenced by it instead?

The description of those sugar plantation zombies by Seabrook gives me chills. Even if they werent real zombies, the conditions must have been horrible.

True, and think about how that ties into modern zombie movies where they often shamble around shopping malls. The metaphor just shifted from slave labor to consumer culture.

I actually visited Haiti a few years ago and learned about real Vodou practices. Its nothing like what Hollywood portrays.

The fact that traditional zombies could be freed when their Bokor died is such an interesting detail that movies never include.

What strikes me most is how the original zombie concept was about the loss of free will rather than flesh-eating monsters.

Reading about Zora Neale Hurston actually photographing what she believed was a zombie is wild. Wonder what happened to that photo.

Im curious about how bokors supposedly created zombies. The powder that simulated death sounds like it could have been a real substance.

The part about them replacing ghosts in American fiction makes sense. People wanted something more tangible to fear.

Anyone else find it interesting that early zombie films focused on the fear of becoming one rather than being attacked by them?

This really shows how Hollywood completely transformed the concept from its cultural origins.

The historical context makes me see Night of the Living Dead in a whole new light now.

Im going to have to disagree about early zombies being scarier. Modern fast zombies are way more terrifying than slow magical ones.

Actually, I think the idea of losing your free will to a Bokor is much scarier than just being eaten by a zombie.

The whole Vodou religion sounds fascinating. Wish the article went into more detail about that.

Never knew Haiti was the first independent black republic. They really glossed over that in my history classes.

I find it disturbing how these cultural beliefs were used to further demonize Haiti after their revolution.

Makes me wonder what other cultural elements Hollywood has completely misrepresented over the years.

The transformation from Vodou spiritual practice to horror movie monster is pretty problematic when you think about it.